The Story of California's Japantowns

The First Issei

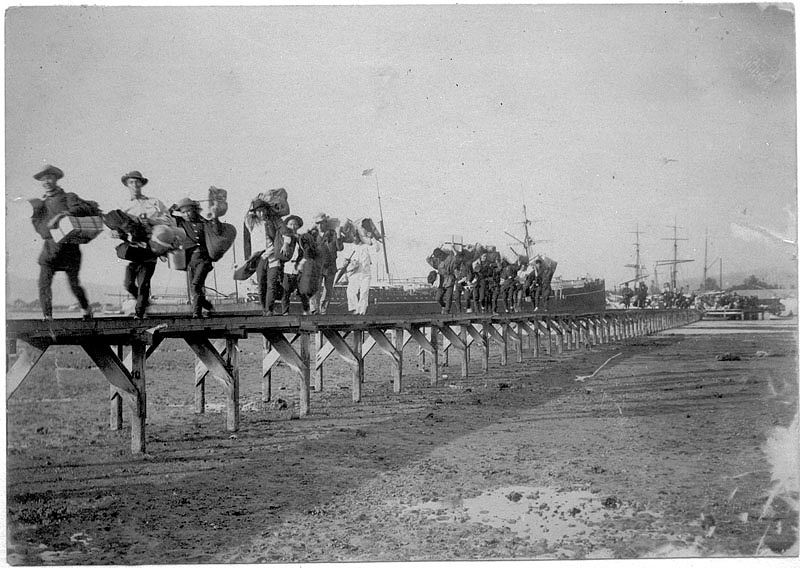

Large-scale Japanese immigration to the mainland U.S. began in the mid-1880s, with "student-laborers" being encouraged by the government to soak up Western knowledge. They soon gave way to economic migrants, mainly from the impoverished northeast Tōhoku region. These early migrants tended to be itinerant workers, only planning to stay in the U.S. for a temporary amount of time. This was often obligated by the contracts that they signed. Sending most of their money home, the main demographic were married men, although there were some young men who settled permanently within the United States, forming the core of an issei generation. They were aided by the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which left a void in the demand for immigrant labor. Nonetheless, they still suffered from a high degree of discrimination, a key impetus in the development of Japantowns.

Large-scale Japanese immigration to the mainland U.S. began in the mid-1880s, with "student-laborers" being encouraged by the government to soak up Western knowledge. They soon gave way to economic migrants, mainly from the impoverished northeast Tōhoku region. These early migrants tended to be itinerant workers, only planning to stay in the U.S. for a temporary amount of time. This was often obligated by the contracts that they signed. Sending most of their money home, the main demographic were married men, although there were some young men who settled permanently within the United States, forming the core of an issei generation. They were aided by the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which left a void in the demand for immigrant labor. Nonetheless, they still suffered from a high degree of discrimination, a key impetus in the development of Japantowns.

Issei Farmers

Although Japanese immigrants were initially tapped as a source of cheap labor in the absence of Chinese immigration, some Issei were able to purchase lands to cultivate. Despite the California Alien Land Law of 1913 heavily restricting the ownership of property by non-citizens, aimed specifically at Japanese immigrants, by 1920, some 450,000 acres of land were growing rice, mulberries, and leafy vegetables. Many of the immigrants had experience cultivating marginal lands, and their ability to transform land that would otherwise be used for grazing into productive farmland was remarkable. In 1940, when the average value per acre of West Coast farms was $37.94, for Issei owned farms, it was $279.96. Issei farmers were disproportionately efficient at their work. In 1940, despite owning less that 10% of California's cropland, they produced 40% of the state's vegetable crop.

Although Japanese immigrants were initially tapped as a source of cheap labor in the absence of Chinese immigration, some Issei were able to purchase lands to cultivate. Despite the California Alien Land Law of 1913 heavily restricting the ownership of property by non-citizens, aimed specifically at Japanese immigrants, by 1920, some 450,000 acres of land were growing rice, mulberries, and leafy vegetables. Many of the immigrants had experience cultivating marginal lands, and their ability to transform land that would otherwise be used for grazing into productive farmland was remarkable. In 1940, when the average value per acre of West Coast farms was $37.94, for Issei owned farms, it was $279.96. Issei farmers were disproportionately efficient at their work. In 1940, despite owning less that 10% of California's cropland, they produced 40% of the state's vegetable crop.

The Development of Japantowns

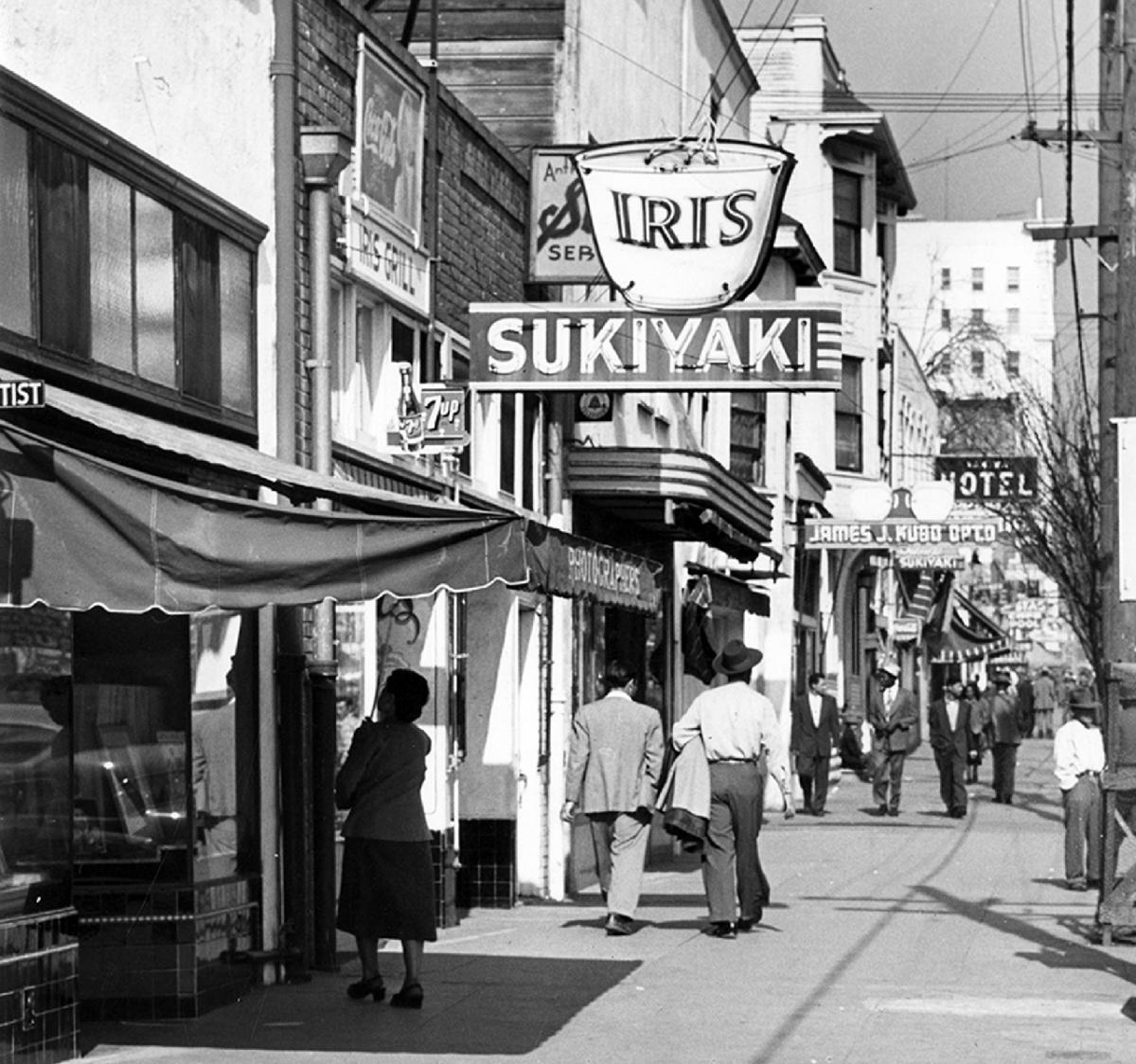

The growth of the Japanese-American agricultural industry resulted in a renaissance in Japantowns. Because of the language barriers that Issei farmers faced, they preferred to sell their produce to Japanese middlemen, who would then carry their products to market. These middlemen setup shop in small to mid-sized farming communities throughout California, serving as nuclei for fledgling Japantowns. Around them, small businesses cropped up, creating a parallel society separate from mainstream American society. These Japantowns served as both a blessing and a curse for Japanese-Americans. They acted as cultural hubs, and provided unique services. However, they were also potent examples, to the rest of American society, of the inability for the Japanese to assimilate.

The growth of the Japanese-American agricultural industry resulted in a renaissance in Japantowns. Because of the language barriers that Issei farmers faced, they preferred to sell their produce to Japanese middlemen, who would then carry their products to market. These middlemen setup shop in small to mid-sized farming communities throughout California, serving as nuclei for fledgling Japantowns. Around them, small businesses cropped up, creating a parallel society separate from mainstream American society. These Japantowns served as both a blessing and a curse for Japanese-Americans. They acted as cultural hubs, and provided unique services. However, they were also potent examples, to the rest of American society, of the inability for the Japanese to assimilate.

The Fall of Japantowns

Japanese-American internment, started upon the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Roosevelt, dealt a catastrophic blow to Japantowns. Internees were obliged to turn their properties over to a trustee for the period of their internment, or, failing that, to sell their properties for pennies on the dollar. It was not just their hosues that were confiscated, Central Valley farmers were among the most vocal advocates for internment. After Executive Order 9066, these farmers were then able to take over the farms that their Japanese competitors had left. During World War II, their now vacant properties were taken over by workers attracted to the well-paying jobs that the armaments and shipbuilding industries provided on the West Coast, changing the demographics of Japantowns, and making it more difficult for their former residents to move back in.

Japanese-American internment, started upon the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Roosevelt, dealt a catastrophic blow to Japantowns. Internees were obliged to turn their properties over to a trustee for the period of their internment, or, failing that, to sell their properties for pennies on the dollar. It was not just their hosues that were confiscated, Central Valley farmers were among the most vocal advocates for internment. After Executive Order 9066, these farmers were then able to take over the farms that their Japanese competitors had left. During World War II, their now vacant properties were taken over by workers attracted to the well-paying jobs that the armaments and shipbuilding industries provided on the West Coast, changing the demographics of Japantowns, and making it more difficult for their former residents to move back in.

The Issei-Nisei Generational Gap

Japanese-American internment also greatly catalyzed the transition from the agricultural Issei generation to the more urbanized Nisei generation. Japanese culture doesn't glorify the life of a peasant, and the rice farmer is quite low on the social pyramid. The Nisei generation had access to American schools and universities, gaining diplomas and skills which couldn't be reappropriated during the years of internment. Following their release, the aging Issei usually chose not to return to the rigors o agricultural life, instead, choosing to follow their Nisei children into the cities. There, the Nisei took up white-collar occupations. It is likely that this transition away from agriculture would have occurred nonetheless without WWII, but the seizing of land and property greatly accelerated this process. For the rest of the 20th century, outside opportunities served as a constant drain upon the Japanese populations within Japantowns.

Japanese-American internment also greatly catalyzed the transition from the agricultural Issei generation to the more urbanized Nisei generation. Japanese culture doesn't glorify the life of a peasant, and the rice farmer is quite low on the social pyramid. The Nisei generation had access to American schools and universities, gaining diplomas and skills which couldn't be reappropriated during the years of internment. Following their release, the aging Issei usually chose not to return to the rigors o agricultural life, instead, choosing to follow their Nisei children into the cities. There, the Nisei took up white-collar occupations. It is likely that this transition away from agriculture would have occurred nonetheless without WWII, but the seizing of land and property greatly accelerated this process. For the rest of the 20th century, outside opportunities served as a constant drain upon the Japanese populations within Japantowns.

The Failure of the Japantowns to Recover

The loss of the agricultural industry struck a blow that Japantowns never fully recovered from. The vast majority of Japantowns, those located within farming communities, shut down altogether, as there was no longer a need for agricultural middlemen if there aren't farmers in the first place. The Japantowns located within urban locales also suffered greatly, as they served as the endpoints of where the middlemen would store and distribute their produce. These Japantowns were forced to make a transition away from the dependency on the agricultural sector and towards tourism, restauranteering, and cultural activities. Ultimately, the loss of the Japantowns did result in a greater degree of assimilation of the Nisei and Sansei populations. The vast majority of Issei passed on their knowledge of Japanese to their children, but following the end of WWII, the heritability of the Japanese language dropped drastically.

The loss of the agricultural industry struck a blow that Japantowns never fully recovered from. The vast majority of Japantowns, those located within farming communities, shut down altogether, as there was no longer a need for agricultural middlemen if there aren't farmers in the first place. The Japantowns located within urban locales also suffered greatly, as they served as the endpoints of where the middlemen would store and distribute their produce. These Japantowns were forced to make a transition away from the dependency on the agricultural sector and towards tourism, restauranteering, and cultural activities. Ultimately, the loss of the Japantowns did result in a greater degree of assimilation of the Nisei and Sansei populations. The vast majority of Issei passed on their knowledge of Japanese to their children, but following the end of WWII, the heritability of the Japanese language dropped drastically.

Philo Wong 2023.